Dear Reader,

The fifth edition of Spotlight looks at the incentives being provided for e-vehicles in India as part of the framework of tackling air pollution.

Electric Vehicles in the National Clean Air Programme and FAME-II: Are We Driving in the Right Direction?

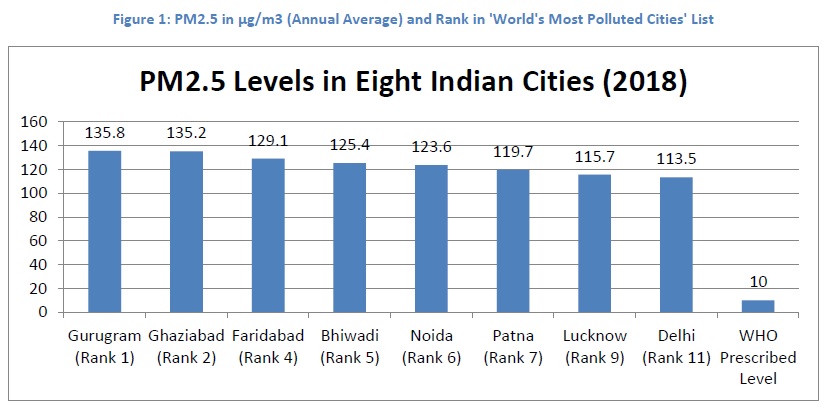

Air pollution is a major cause for concern every winter, when Delhi closes down again. However, despite Delhi’s habit of hogging the limelight, AirVisual’s 2018 analysis of PM2.5 in 3,000 cities worldwide showed that 22 of the top 30 cities in the ‘Worst Air Quality’ list were in India.

Transport pollution is receiving significant publicity in this regard, including the snappily-named FAME schemes designed to increase uptake of electric vehicles in India.

The National Air Monitoring Programme (NAMP) has found over the years that particulate matter (monitored as PM10 and its subsection PM2.5) is the major existing issue in India, with the other major monitored pollutants including NOx, SOx, and Ozone being within prescribed guidelines. As the National Clean Air Programme Report describes, overall (that is, looking at national estimates) residential and industrial are the dominant forces in PM2.5, with vehicular emissions contributing a low 4% of PM2.5 estimates. At a fine-grained level, there are estimates that vehicular emissions contribute a larger amount to PM2.5 concentrations in urban areas and worsen local pollution levels, particularly in winter.

Moreover, vehicular emissions are a dominant cause of NOx emissions, contributing 35% of pollutants, and which may lead to higher PM2.5 concentration due to secondary pollutants formed from chemical conversions. Even if this is not a major issue yet, it should be dealt with pre-emptively.

Electric vehicles are being increasingly touted as the sustainable alternative to pollution fossil fuel-based transport but in the enthusiasm, there seem to be some missing links in the chain.

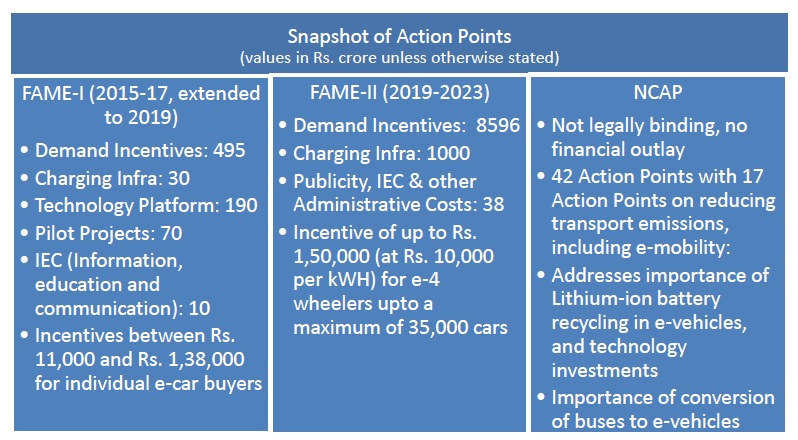

FAME-I, FAME-II, and the National Clean Air Programme: A Snapshot

Analysing the Action Points

Demand incentives: While FAME-I has not yet had a thorough report card, it must be noted that only 1200 e-car units were sold in 2018 (a 40% decline from the previous FY), and a mere 3,600 units in 2019. On the other hand, electric two-wheeler sales increased 138% in 2018 and 140% in FY 2019. It is significant, and a step in the right direction, that under FAME-II the cap on e-two-wheelers and e-three-wheelers to be supported is higher than the cap on e-four-wheelers, but the number of e-buses (which provide the greatest number of seats per km travelled) to be supported is fairly low, perhaps due to cost. Moreover, the indigenous parts requirement for two-wheelers may actually reduce sales, as they may untenably raise the cost of the battery and subsequently the vehicle.

Charging infrastructure: This is a major cost and point of worry for both manufacturers and buyers, and under FAME-II still has relatively low levels of financial outlay. Addressing the importance of making available low-emission or zero-emission charging facilities is key to reducing emissions and increasing electric vehicle uptake. It is essential that the source of electric vehicles be non-polluting, else we are simply transferring the emissions to a different stage of the process. Moreover, the charging process can take up a significant portion of time, and the infrastructure must address the now-chronic parking shortages in Indian cities.

Research (Technology Platform and Pilot Projects): FAME-II is no longer providing specific incentives for such research work. As Li-ion batteries are a thorn in India’s side, and likely to remain so, research incentives for alternatives that are more sustainable and can be developed indigenously is an area that the government is ideally suited to take up. The government is pushing for indigenous manufacturing of e-vehicles, and batteries in particular, but this may not be the most effective use of government resources. The larger battle is in developing a battery that is not dependent on Lithium, where India’s manufacturing sector may already be at an irrevocable disadvantage.

Consumer education: Consumer education should not only focus on shifting to electric vehicles. The major need is to reduce the concerns of status and concerns with public transport that promote private vehicle usage. Environmentally sustainable public transport that reduces the number of vehicles on the road is necessary and a combination of reliability, cost-effectiveness and consumer education is required.

The National Clean Air Programme: While the NCAP cannot be directly compared to FAME-II, as it has a broader mandate, but it demonstrates a holistic view of the needs of both mobility and e-mobility planning in India, showing that there is an understanding of the needs of transport emissions reduction, but backing only for some areas. The NCAP has no legal or financial backing as of now.

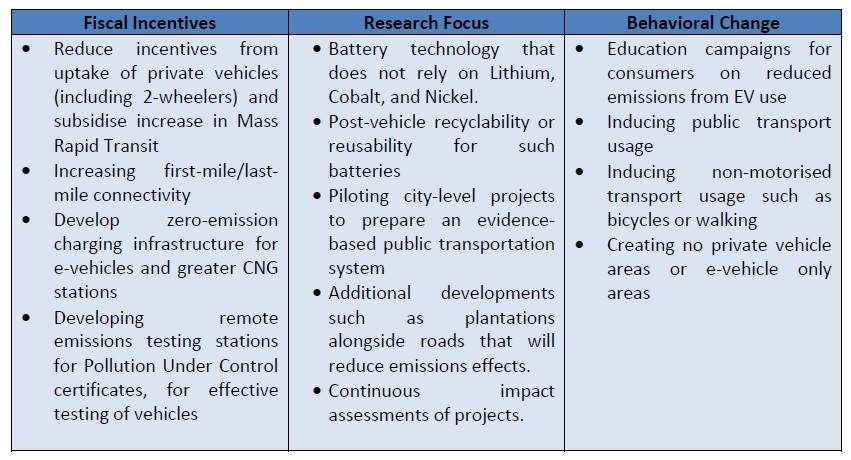

While many European countries have utilized fiscal incentives to drive up e-vehicle adoption, it must be noted that car usage in India is famously low at only 23 per 1000 individuals. We should take advantage of this. Incentives to take up e-cars may become perverse incentives, leading to behavior such as buying multiple vehicles, buying of private vehicles by people who otherwise would not have, etc. A Jevons paradox situation where government policy leads to an overall addition to the number of vehicles on the road may lead to a situation where the traffic is untenable and the pollution has not decreased overall.

It should be considered, in this light, whether incentives that are intended to increase uptake of personal vehicles (as some of FAME-II is) is an appropriate policy that will lead to our overall goal of reducing emissions reductions. The argument may be that in some cases, such as with electric-two-wheelers, they may replace ICE vehicles instead of increasing the number of vehicles overall. Even in such cases, it should also be considered whether demand incentives are the most appropriate policy for the government to reduce vehicular emissions. If there is a business case for e-vehicles, the private sector is capable and the appropriate party to take it up. The government’s energy and money may be better-served in other areas, including planning, piloting and implementing sustainable transportation policies.

Fuelling Our Future

A mix of incentives and behavioral change inducements can develop a holistic mobility system throughout India that is sustainable and reduces emissions, as well as other problems that are cropping up in transport such as traffic congestion, parking space issues, and lack of street space for walking/non-motorised transport. Many of these suggestions are already well-known and identified but may not be receiving the proper push.

Food For Thought

Are we falling into a trap of producing attractive plans at the policy level that are ultimately unable to solve the essential problem?

What are the appropriate areas for governments to invest in, in order to provide a sustainable solution?

Along with technology solutions, how do we ensure enthusiastic uptake of sustainable mobility by citizens?